Walkers in Wytham Woods are helping to understand fungi and climate change

This blog is long overdue; I promised to write it in January. What’s inspired me to get tapping on the keyboard today is that yesterday I had the privilege of seeing Merlin Sheldrake speak in the morning, and watched his film (narrated by Björk!) in the evening. For those of you who don’t know the name, Merlin Sheldrake is a young mycologist who, in 2021, authored one of the best-selling, most approachable and thoughtful books on fungi that I know of, which has been widely read and well-publicised by the media. Hearing him talk yesterday made me eager to share my love of fungi with as wide an audience as possible, turning this long-promised blog into an opportunity rather than another chore on the to-do list.

I’ve been interested in fungi since my undergraduate days, and undertook my PhD in the ecology of rare wood-decaying fungi. Since then, although my jobs have never been directly involved in fungi, I haven’t been able to escape my fascination with this vital, but often misunderstood and overlooked group of organisms which is so essential to the world around us. I’ve worked increasingly with people and nature, recognising that if we want to protect the natural world, we need people to care passionately about it, and have the opportunities to get close to nature. With this in mind, I was excited to set up a citizen science project in Wytham Woods that encourages visitors to get up close with fungi.

What are fungi?

A little reminder of what fungi are – we’re talking about an entire separate kingdom, actually more closely related to animals than plants, with which they are often grouped. There are estimated to be at least 2.2 million species of fungi, with only 8% of these species known to science. They include species as diverse as athlete’s foot, baking yeast, button mushrooms, and the iconic red and white fly-agaric mushroom. The showy mushrooms, puffballs and brackets that we see are simply the reproductive structures of fungi, known as fruit bodies, the main part being a network of thread-like tubes called hyphae, known collectively as mycelium. Fungi are master explorers, the fine mycelium penetrating dense, complex materials in search of food, water and mates; it is this lifestyle that allows fungi to play such important and unique roles in the world around us. For example, around 90% of plants have an association with mycorrhizal fungi, in which mycelium grows around or into the roots, foraging for nutrients, helping obtain water and defending the plant against pathogenic fungi. In return, the plants give the fungi food, sharing up to 20% of the food they make for themselves through photosynthesis with their fungal partners. Examples of mycorrhizal fungi are the poisonous fly agaric mushroom, and the oft-foraged chantarelle. Other fungi, called saprotrophs, get their food from breaking down dead organic matter. These fungi are some of the only organisms that can break down the complex chemistry of wood, turning what is for us a hard, inedible material into food and in the process recycling valuable nutrients that would otherwise remain locked up in the wood, unavailable to other plants – they are nature’s recyclers.

A little reminder of what fungi are – we’re talking about an entire separate kingdom, actually more closely related to animals than plants, with which they are often grouped. There are estimated to be at least 2.2 million species of fungi, with only 8% of these species known to science. They include species as diverse as athlete’s foot, baking yeast, button mushrooms, and the iconic red and white fly-agaric mushroom. The showy mushrooms, puffballs and brackets that we see are simply the reproductive structures of fungi, known as fruit bodies, the main part being a network of thread-like tubes called hyphae, known collectively as mycelium. Fungi are master explorers, the fine mycelium penetrating dense, complex materials in search of food, water and mates; it is this lifestyle that allows fungi to play such important and unique roles in the world around us. For example, around 90% of plants have an association with mycorrhizal fungi, in which mycelium grows around or into the roots, foraging for nutrients, helping obtain water and defending the plant against pathogenic fungi. In return, the plants give the fungi food, sharing up to 20% of the food they make for themselves through photosynthesis with their fungal partners. Examples of mycorrhizal fungi are the poisonous fly agaric mushroom, and the oft-foraged chantarelle. Other fungi, called saprotrophs, get their food from breaking down dead organic matter. These fungi are some of the only organisms that can break down the complex chemistry of wood, turning what is for us a hard, inedible material into food and in the process recycling valuable nutrients that would otherwise remain locked up in the wood, unavailable to other plants – they are nature’s recyclers.

Fungi and climate change

As with other wildlife, fungi and the roles they play in our natural world are currently threatened by climate change, not to mention factors such as habitat loss, nutrient deposition and the spread of non-native species. Unfortunately, our knowledge and appreciation of this group lags far behind that of more charismatic organisms, such as oak trees or eagles. We do know that the fruiting patterns of many species of fungi are changing, with fruit bodies popping up over a longer season in some cases, in others simply appearing earlier or later, shifting the window of when mushrooms are seen. This matters because if reproduction is changing, the mycelium may be changing their habits too, with knock-on effects in the ecosystems where they are supporting trees and plants, recycling nutrients, and also causing disease. We need to know more about what species are producing mushrooms when, so that we can understand how fungi are responding to climate change.

The public can help

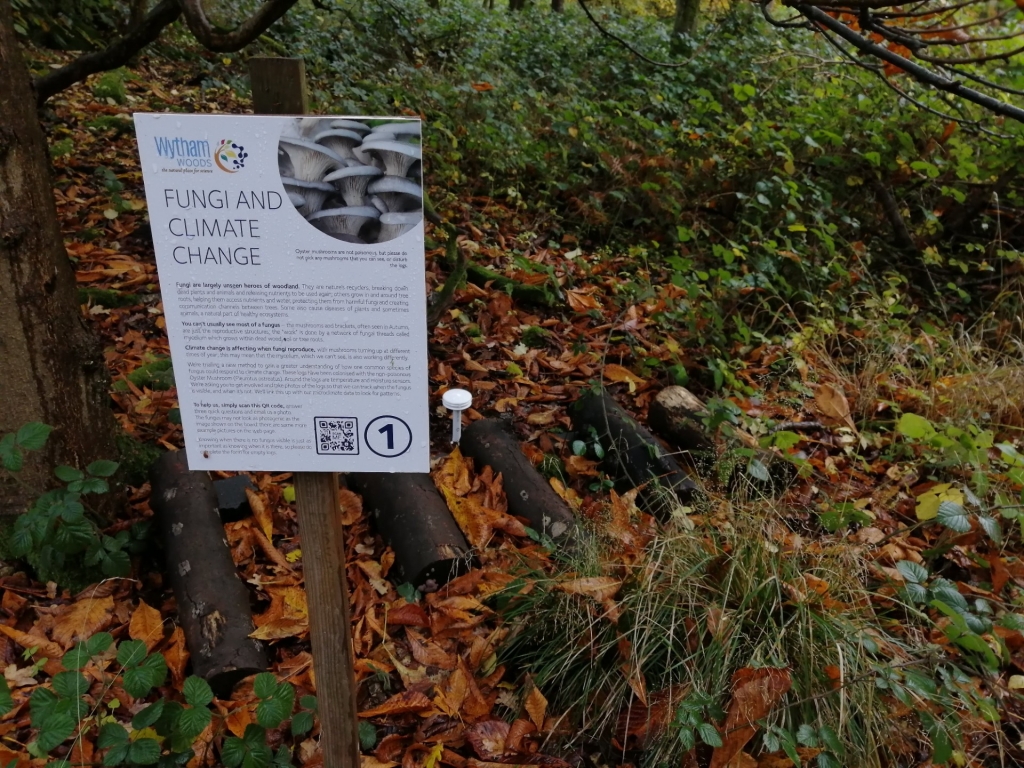

In order to trial a new fungi citizen science methodology and hopefully understand more about how one species might respond to climate change, we set up an experiment in Wytham Woods. We took cultures of a native strain of the non-poisonous oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus and inoculated a number of logs with it. We kept the logs in a cool, covered, ventilated outdoor space for several months to allow our fungi time to grow out into the wood, establishing itself in the logs. We then placed the logs at two stations in Wytham Woods. The plan is simply to see when oyster mushrooms appear on the logs. This should happen when the mycelium has had time to grow through enough wood to have sufficient energy to “invest” in producing mushrooms, i.e. reproduce. When the mushrooms actually appear depends as well upon the local microclimate, i.e. temperature and moisture. With logs in different locations and temperature and moisture sensors with them, we can understand how different micro-environmental conditions influence fruit body production, relating that to predicted future climatic changes. By having our inoculated logs, there is one location where we know the fungi COULD be – there is no need to scour the forest searching for elusive evidence. Importantly, by asking participants to submit data whether or not fungi are present, we can collect data on when they are not there, thus being sure that a lack of fruit body sightings is not simply because people haven’t been looking there. In having people take photographs several times a week, we have evidence of absence, which is so important.

What we’ve found, and how you can get involved

I’ve been delighted and touched at how many people have contributed to the project so far, with over 150 individual data points to date. Although we’ve not seen any oyster mushrooms appearing yet, what we’ve been able to show is that this surveying method works – we have observations on a regular-enough basis so that if oyster mushrooms had appeared, we would certainly know about it. What we do have are lots of King Alfred’s Cakes Daldinia concentrica; a wood decay species that only grows on dead ash. It looks like the oyster mushroom mycelium with which we inoculated the logs didn’t get a strong enough foothold to out-compete the propagules of King Alfred’s Cakes fungi that would already have been present in the logs.

There is huge potential for citizen science to contribute to fungal conservation and research. The method of using QR codes to obtain citizen science observations of a given location is increasingly being used, and could be a valuable tool for mycologists. It could be used to understand whether a re-introduction of rare fungi had been successful, or to simply monitor fallen dead wood to understand what species are appearing over what time scales. In our case, we very much hope that we see some oyster mushrooms in autumn 2024 (which may still happen, despite the King Alfred’s Cakes!). In the meantime, if you’re out in Wytham Woods, please keep sending us your observations of the logs – it’s all useful, whether or not our target species is present! The logs are situated in two locations along the main path from the Sawmill towards the Chalet. And any time you’re out in nature, do keep an eye out for any fungi; sharing images on social media or with friends, or simply observing them for your own pleasure is all part of increasing our appreciation of this incredibly incredible group of organisms.

Other recent stories